Diamondback’s new bike is the fastest bike in the world. Really. Flipping the world of bike engineering on its head, Kevin Quan and his team of engineers designed the Andean from the wheels up to create the most aerodynamic bicycle in the world.

“We set out with Kevin Quan Studios to build the fastest triathlon bike on the market, with no concern for the arbitrary limitations placed on bicycle design by the UCI,” said Diamondback product development VP Michael Brown. “Our Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analysis and unique, best-in-class wind tunnel testing at the University of Toronto shows that we’ve succeeded in that endeavour.”

Kevin Quan, for his part, told Trizone he first started designing bikes in 2003. “From 2003 until 2008, I was senior engineer at Cervelo,” he said from the Paradise Bar in Kona.

“I was the product lead for the first carbon P3 and the first S-bikes, the first carbon S-bikes,” Quan said, adding that in 2008, together with two colleagues he launched his own design studio in Toronto. “One of my first customers was Diamondback.”

Quan emphasised that his key strengths centred purely on the design side of products. “CAD is just a tool that we use to communicate to the manufacturing [division] what we’re actually trying to describe,” he said. “It’s just like a pencil for an artist; they’re experts in the pencil [itself] but that’s the tool that they use.”

Flipping the world of bike engineering on its head, Diamondback, along with Kevin Quan and his team of engineers, designed the Andean from the wheels up to create the most aerodynamic bicycle in the world. “I have an industrial designer and we have five engineers,” he added. “We started with the [former] and I said: ‘How about it? Give me whatever crazy things you think’.”

Quan said that this process yielded a myriad of potential design ideas and prototypes, in fact far too many from which to select. “I then drew on my experience recently of designing wheels and said that from an aerodynamic standpoint are very difficult to optimise in the middle part,” he added.

“The top and bottom are already aerodynamically efficient, but the middle part isn’t, and that’s where we started,” explained Kevin.

“I said to my designer: ‘Give me a silhouette that looks really good, but fills up… so there’s no space. Then we can make the fastest bike in the world.’” And Kevin’s designer did exactly that, and once the drawings were read, he just said ‘That’s it!’

Designing the bike according to a systemic approach, the Andean was made by fully integrating HED’s Jet 6 Plus wheels into the frame design, planning for a 24mm tire in the front and 26mm in the rear. Due to its ‘from the wheels up’ approach, the frame was created with an ‘Aero Core’ design to minimise drag, and has a unique inbuilt storage system that’s helping make the classic strap-on nylon bags redundant. While the final design aspects sound straight forward, it’s the remarkably complex scientific methods used in creating the Andean that have produced the world’s fastest road bike.

Software Calibration Gives Kevin a 2 Year Lead on any Competition

Kevin Quan’s engineering studio uses the complicated fluid dynamics of other firms as well as the KS1 model, but it’s their unique software calibration and laser diagnostic testing that enabled the birth of the Andean.

It began with a four-year collaborative project over the past two years involving Dr. Philippe Lavoie of the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies (UTIAS), his graduate students and their half scale wind tunnel.

“The tunnel has a rotating table, drums to spin the wheels and it’s all calibrated to the forces of bicycles. We built 50% scale models, including a rider,” explained Kevin. “This is where most other companies stop. They accept the numbers from their software and create a product from there.” But Kevin and his team pushed further.

“After getting numbers from the model in the tunnel, we fed those back into the software so it could become more predictive. You want to have an iterative cycle where you get your wind tunnel results, then calibrate your software to where they match.”

This approach meant Kevin Quan’s software had become predictive to the most precise degree. “It’s our trade secret. It’s not about the software we’re using, it’s that we put in the time to make it reflect what it is in the real world,” he noted. By utilising laser diagnostic testing, the researchers were able to measure the flow around the frame, plus the field of flow around specific elements like the cockpit, rear triangle and bottom bracket.

Rather than hinder development, the tunnel’s half scale size was of huge benefit. Due to the scaling of the tunnel, the team were able to adjust the turbulence more precisely, which helped them replicate both real world weather conditions as well as a raft of different riding conditions such as riding solo, in front of the pack and at the back of the pack.

“Often, manufacturers look at the frame in a vacuum without consideration for how it interacts with the rider or other components of the bicycle. By taking the integrated design approach, we were trying to see the rider and bike as the wind does – one unit fighting against aerodynamic drag,”said Diamondback.

It’s this unique approach to problem solving and design, along with his canny ability to turn everything on its head and create his own approach that has led Quan to create the fastest bike in the world. Although it’s fair to say he did have some pretty brainy help.

“We have a professor and grad students who have to get all the details right. If they publish in the academic world, it has to be spot-on! It’s not like other companies who cut corners to get market research, this was academically based,” he said.

Project Runway for Bike Design

Chatting with Kevin, you get the feeling you’re speaking with a true genius who’s been in the bike engineering game a while. It’s been a two year process to create the Andean. “It’s a bit like Project Runway,” said Kevin, describing the process of designing the world’s fastest bike. With so many different bike-related sports, it was Diamondback’s own history that started the journey towards the Andean.

“Phil Howe, President of Diamondback, was a finisher at Kona in the 80’s,” noted Kevin. “He was really keen to do a triathlon-specific bike.” This, plus Diamondback’s purchase of the Centurion line of triathlon bikes provided the final direction Kevin needed to get started. But they needed a point of difference, so they asked the athletes what they needed.

“Other brands survey ten of thousands of age groupers and riders, but we just wanted to ask the best,” continued Quan. “We sent out surveys to Diamondback’s three triathletes who then forwarded it to their peers. They told us it was all about the container. They wanted more stuff so they could self sustain for the whole race.”

Eager to move past the standard nylon bags with zippers athletes usually fill with their in-race nutrition, Kevin went to work on customising injection moulded plastics, rubbers and magnets to create storage boxes that become part of the bike. He succeeded, and the Andean allows riders to carry three water bottles, three bars, ten gels and an extra tube. By integrating usability with design, Kevin has created the difference that really helps athletes improve their longevity, without compromising on the all-important aerodynamics.

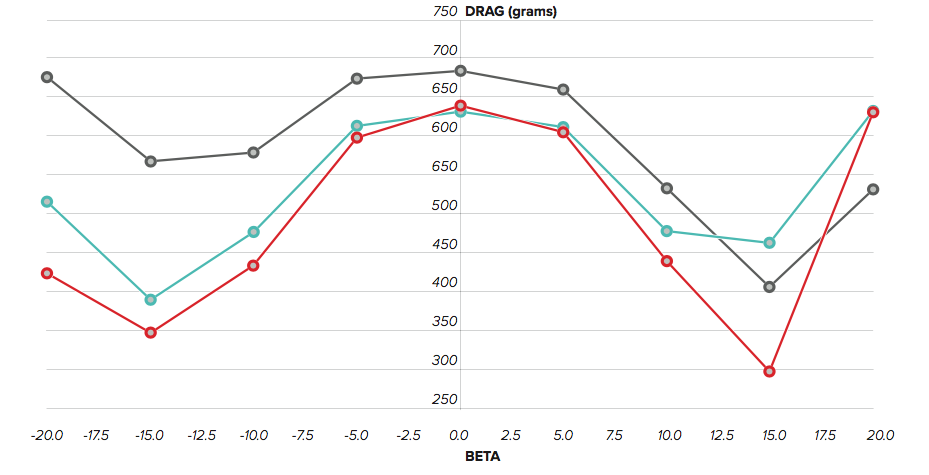

For those that love data, here’s how the bike performed in the wind tunnel

Run 1 (gray line)

This is the baseline test using a Diamondback Serios with HED Jet 6 wheels front and Jet 9 rear with Continental Attack/Force tires (22mm and 24mm), HED Corsair Aerobar, with no storage components. The Serios has been tested in the past against industry benchmarks such as the Cervelo P5 and Trek Speed Concept. The Serios’ strength is high yaw performance – almost 33% faster at 15 degrees yaw vs the competition but gives some back at zero yaw (about 5%)

- Serios Baseline W

- Front Wheel: Hed Jet 6

- Rear Wheel: Hed Jet 9

Run 2 (turquoise line)

This is a comparative test of the new Diamondback Andean with identical setup to the Serios Baseline. The Andean was designed to surpass the competition at low yaw while maintaining the large advantage at high yaw that the Serios displayed. This successful test con rms that the Andean is 10% faster at zero degrees than the Serios and an even more impressive 32% less drag at -15 degrees. This is completely attributable to the Aero Core and fairing of the crank.

- Andean Baseline

- No Storage W/

- Front Wheel: Hed Jet 6

- Rear Wheel: Hed Jet 9

Run 7 (red line)

This is a ‘fastest con guration’ test of the Diamondback Andean with HED Jet 9 front wheel, HED Jet Disc, Force/Attack tires, HED Corsair, and Andean Storage accessories. In this con guration, competitive triathletes can store a full race compliment of food and liquids while maintaining industry leading aerodynamics. The Diamondback Andean demonstrates that it is truly the fastest triathlon bicycle in the world.

- Andean Baseline

- Full Storage

- Front Wheel: Hed Jet 9

- Rear Wheel: Hed Jet Disc

Kevin’s Biggest Tip for Purchasing a Bike

Start with the tyres, then the wheels, then the frame then the rest of the bike. “A lot of consumers do everything backwards, starting with the bike, then wheels. Because of the inflation and size changes from a 25mm to 28 once inflated, you should really start with the tyre.”